A study in scarlet - painting with historical reds

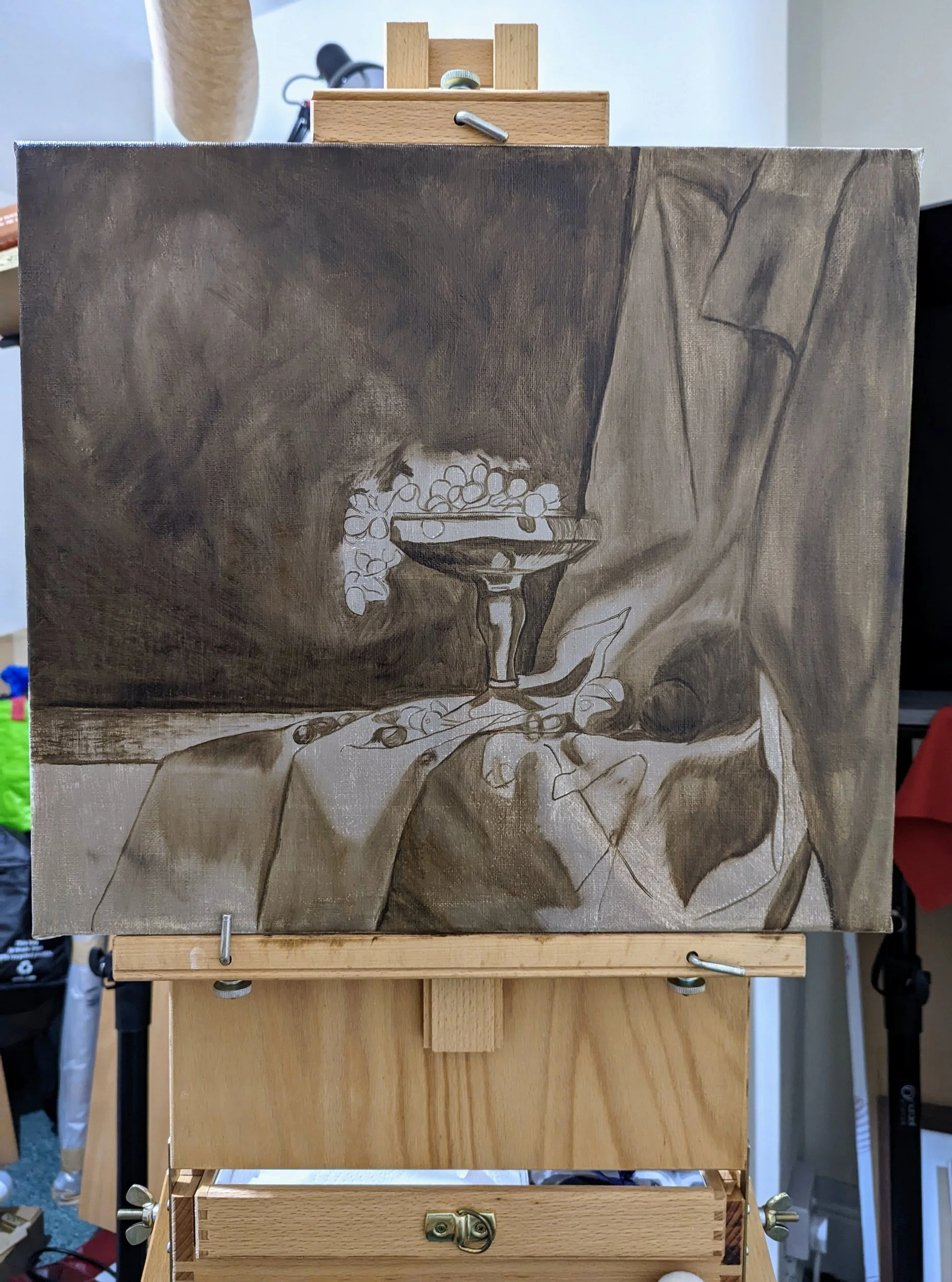

“Red 1” - Angus Mathieson 2022. A still life study of some grapes and plums, sitting on a piece of red drapery. Part of a series of still life paintings - each one highlighting the power of a set of historical pigments.

Learning from an Old Master - Jan van Eyck

As part of my new series - a set of almost monochromatic still life paintings created to demonstrate the beauty of natural pigments (many of which are seldom manufactured, let alone used today) I began with some research into the handling of these now archaic colours.

The first in the series is an arrangement designed to exhibit the beauty of one of the most important pigments in the history of art - vermilion. However, vermilion (mercury sulfide) is known to darken with time. It is naturally fugitive in ambient light conditions. (Perhaps in a future post I will outline the scientific reasons behind the chemical transformations of this pigment causing it to change over time). It therefore requires a more careful approach than the light-fast, modern synthetic alternatives.

The old masters were well aware of this effect however, and employed specific techniques to reduce the degradation. Not only does the approach I will discuss below help reduce the fading of vermilion, it also significantly enhances the depth and vibrancy of the red. Think of Rubens’ Descent from the Cross or Van Eyck’s utterly sumptuous Virgin with Chancellor Rolin. Yes - that is the red I’m after. For demonstrative purposes, I will be highlighting notes that were taken by conservators during the restoration of Van Eyck’s ‘Margaret, the Artist’s Wife’ at the National Gallery, London.

Jan van Eyck, 'Margaret, the Artist's Wife', 1439.

Restored in 2009 and a great case study for learning how the old masters used red pigments that have remained vibrant, without fading, for centuries.

Image in the public domain.

The technique is based on glazing. Glazing is an (often misunderstood) technique used in oil painting. It involves applying a very thin, translucent layer of colour over another layer of dry paint underneath. This gives rise to a number of beautiful effects such as optical mixing, smoky shadows, and rich gem-like colours. It is the mastery of glazing that makes some of those magical paintings on gallery walls appear as though they have their very own internal light source, or are made with precious rubies or sapphires. The benefits of glazing in the case of vermilion is actually two fold; not only does the upper layer enhance the depth of the red colour, it also acts as a barrier against the environment - protecting the vermilion underneath from darkening with time.

To achieve this, an underpainting must be completed and dry before the glazing process can begin. An oil painting (painted in the historical, indirect method) typically comprises a number of layers. This of course varies significantly from artist to artist, and even from painting to painting, however it can be broken down loosely into the following stages:

1) The ground - a uniform layer of paint, typically a mid tone of neutral grey or earth tones.

2) The grisaille - a loose, monochromatic study of the final composition undertaken typically in shades of brown (brunaille), grey (grisaille), or even greens (verdaccio). This is done to establish the values of light and dark globally throughout the composition.

3) The ébauche - not always used, some artists jump straight to the final chroma of colours. However, this is a useful step for our discussion below. The ébauche involves applying a paint layer in under-saturated colours. (I personally love this technique).

4) Top layers - typically comprising multiple scumbling and glazing techniques, layering colours on top of the layers below.

In the analysis of ‘Margaret, the Artist’s Wife’, multiple paint layers are detected. First is a chalky ground, on top of which a loosely modelled layer can be seen using X-ray imaging.

X-ray image of the underpainting in Van Eyck’s Margaret, the Artist's Wife'. Image from the National Gallery, London.

The X-ray image here shows some loosely painted brush strokes in which Van Eyck roughly maps out his composition in a thin underpainting. Cross section microscope images then show that this particular area of the red dress, the underpainting includes a very thin layer of vermilion - indicating that Van Eyck probably worked with an ébauche in this region; a thin, under-saturated painting of the dress in a low intensity shade of red.

Van Eyck would continue working in desaturated reds, using vermilion with touches of lead white or bone black to adjust the value accordingly to complete the modelling of the dress. Once happy with the design, it would be set aside to dry awaiting a thin veils of red lake pigment to be draped/glazed over the top.

This is exactly what can be seen in the images here showing cross sections of a flake of paint taken from the dress. Looking at the first photograph, a clear band of light red can be seen over a bulky white layer. This is the vermilion underpainting laid on top of the chalky ground and possibly a greyscale grisaille. In the second photograph (the flake split in two in this study) the layers painted on top of this underpainting are seen. They comprise translucent red pigments. When viewed with ultra-violet light (which causes some fluorescent emission) the conservators were able to distinguish three glaze layers, with a thin layer of varnish between the final two coats. The addition of the varnish layer was probably done to saturate the colours before the final coat and add some extra gloss and translucent intensity to that area.

So what red pigment did Van Eyck use for these glazing layers? The conservators used a high performance version of chromatography (yes, the same technique you used in school chemistry lessons with ink) to distinguish two separate lake pigments. The glaze comprised mostly carmine lake - a pigment made from a crushed red insect, the Kermes vermilio Planchon. It also contained some red madder - a pigment obtained from the root of the madder plant. At the time, carmine lake was the most expensive red pigment on the market. Not only did it require collecting large masses of the kermes insect, but a “tour de force” to quote Philip Ball of medieval alchemical chemistry to produce the final pigment.

The question that many ask is “why not just paint directly with these luscious red pigments?” Well, part of the reason lies in the point above - the cost. Given that this pigment costs almost the same as its weight in gold, it would be foolish to use it during the early stages of the painting when working out the composition and creating & erasing mistakes - pentimenti. It makes much more sense to save a very small quantity of it for a very thin final layer - reducing how much of the material is needed, while still harnessing its beautiful colour. The second reason is its translucency. Lake pigments are some of the most translucent colours available in oil paint. This makes them extremely well suited to glazing since it allows light to pass through while imparting its colour on the reflected light - giving rise to the optical mixing mentioned above - acting like a stained glass window. However, it also makes them unsuitable for underpaintings since an element of the painting layers beneath, including drawings and pentimenti will show through - unless you pile thick blobs of paint on, in which case again, would cost a fortune unnecessarily. Vermilion in contrast is extremely opaque - which makes it perfect for working up the majority of the picture.

The final technique employed by Van Eyck during this glazing process, is using it to adjust the shadows on the dress. Although the majority of this modelling is typically done during the underpainting stages, adding small quantities of darker pigments to the glaze layer with the red lake can really enhance the quality and depth of the shadows. To achieve this, Van Eyck mixed in extremely small quantities of ultramarine blue and bone black into the glaze over the areas of shadow to reinforce the folds of the dress. The addition of ultramarine blue (also an incredibly expensive pigment made from the semiprecious stone lapis lazuli) adds a subtle yet beautiful effect of optical mixing - with the blue glazing combining with the red underpainting to add a touch of purple to the shadows. This marks Van Eyck out as being well ahead of his time. The concept of shadows containing colour, rather than simply being darkened with black or dark brown, is one of the philosophies that underpinned the Impressionist movement 400 years later!

Cross section microscope image of a sample taken from the red dress. Image shows a thin layer of vermilion applied over the chalky ground. Image from and owned by the National Gallery, London.

Cross section microscope image of the upper layers of the sample from the red dress. Image shows glazing layers of a red lake pigment over the vermilion underlayer. Image from and owned by the National Gallery, London.

Applying the lessons from Van Eyck

Having highlighted some of the techniques used by Van Eyck in ‘The Artist's Wife’, I will briefly demonstrate below how this knowledge is translated into my own work. The painting is part of a new series I am working on, which will be a collection of still life paintings, each designed to demonstrate the power of an individual colour. The one I will talk about here is designed to highlight the beautiful variations of red.

The ground of this painting is comprised two layers - as per many classical treatises on painting. After sealing the canvas with rabbit skin glue a thinnish ground containing earth pigments in linseed oil is applied followed by a thicker layer (applied with a knife) containing mostly lead white, chalk, and some earth pigments. This gives a beautifully neutral and relatively smooth surface to paint on. The colour can be seen showing through in the bottom left corner of the first image.

On top of this layer a grisaille is completed (perhaps more strictly speaking brunaille) using raw umber. I opted for raw umber here for two reasons: 1) it is incredibly fast drying meaning I can progress to subsequent layers quicker, 2) it is slightly cooler that burnt umber. Having a cooler underpainting will subtly emphasise the warmth of the red upper layers later on - a technique that you see a lot in the work of Rembrandt and Titian. Cool next to warm next to cool and so on.

Using the grisaille as a guide, I then proceed to refine the underpainting adding more and more vermilion into the mix to start working out the chromatic aspect of the composition in addition to the value range. You can see this progress in the second picture. At this stage, I don’t concern myself too much with the highest highlights of the painting - the mid tone of the ground is adequate at this stage for the lighter portions of the composition. Furthermore, adding too much white to the vermilion is known to exacerbate its darkening in time, since it increases the amount of light scattering within the paint layer. However, I do add small quantities of ivory black to start pushing the shadows deeper. This process can be seen beginning in the second photograph and finished in the third. The saturation of the red colour in the drapery is still slightly less than I plan for the final colouring, since this will come from the next step - the glazing.

The fourth picture shows the painting after the application of a glazing layer with cochineal lake. Look at how rich and deep this makes the reds of the drapery!

The final stage, again as per Van Eyck’s technique is enhancing the shadow regions, between the fruit and the folds of the drapery (as seen in the final picture). For this, I delicately applied thin glazes of ultramarine blue and ivory black. In certain lights the very subtle touches of purple come through in the shadows - a really rich and beautiful effect. Something also, that should stand the test of time.

Want to see more?

You may also like:

References

With thanks to the National Gallery London. Link to the original article on Van Eyck’s painting can be found here.

Comments or questions?

Please do leave them in the comments box below!